Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

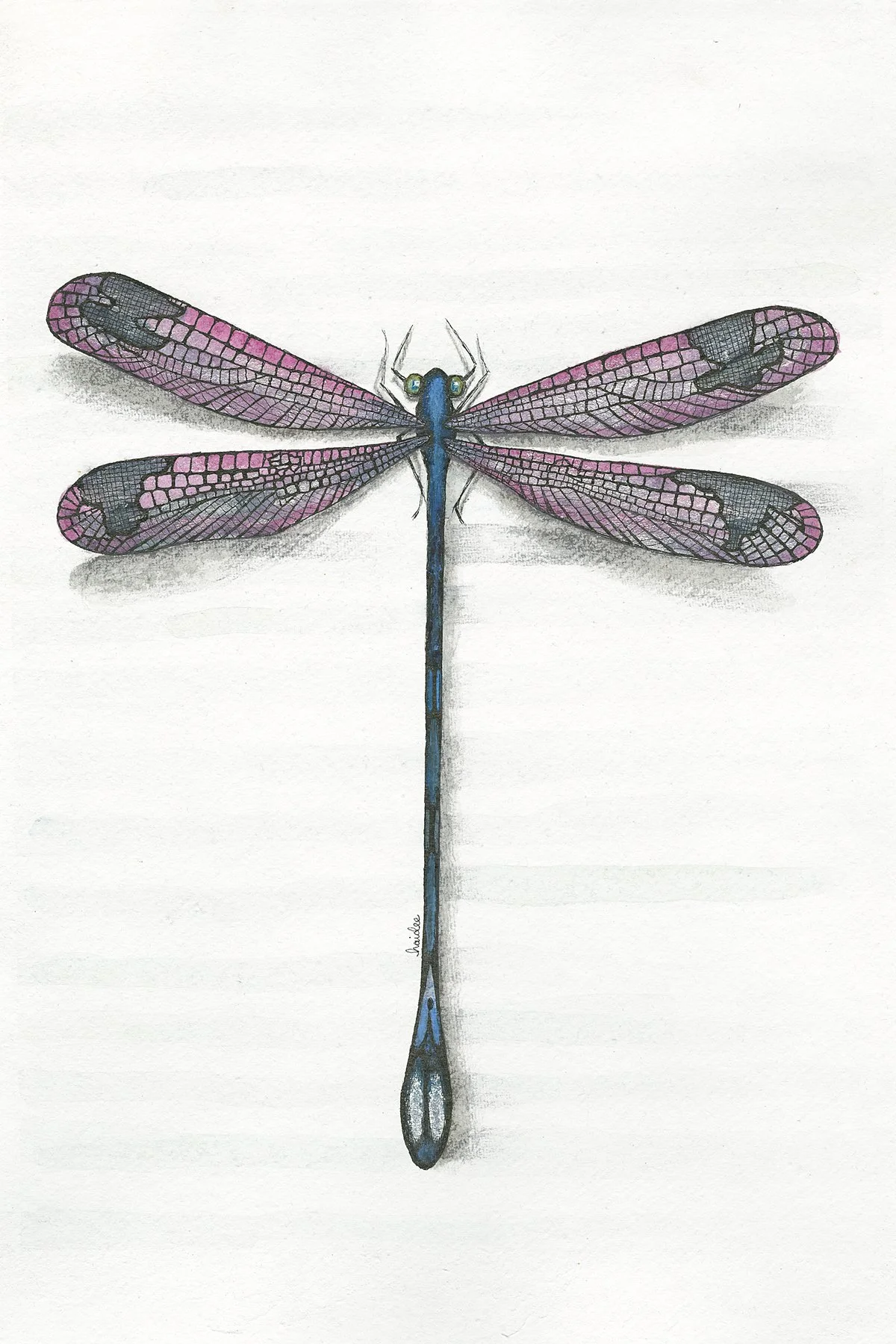

Specimen No. 137 The Rosy Lacewing of Zelenograd

Specimen No. 137

Name: The Rosy Lacewing of Zelenograd | Libellula rosaphasma

Discovered By: Professor A. Otis Larkin

Date of Discovery: 12 July 1912

Locality: Zelenograd Marsh, Eastern Carpathians, Russia

Catalog No. FD - 24 - 137

12 July 1912, at the edge of Zelenograd Marsh in the Eastern Carpathians, Professor A. Otis Larkin of the Linnaean Society chanced upon an extraordinary dragonfly.

Larkin was a stocky Englishman with an archetypical tweed cap and a penchant for quantum-like footnotes in his journals. He was, by temperament and reputation, the sort of naturalist who married precision to theatricality. His presence at this particular spot was to officially assist Russian counterparts in cataloguing wetland Anisoptera but privately he pursued the rumor of swamp orchids and other fancies whispered in correspondence between Russian and Scandinavian field naturalists. It was on this steamy summer morning, face down in the bog, that Larkin caught sight of a pink shimmering flit above the reeds. He watched, astonished, as the creature alighted on a silver-birch leaf, its gossamer wings catching the dawn light. Intricate veining and lace-like filigree etched into translucent rose-pink membranes were like nothing he’d ever seen.

The Professor was fascinated by this dragonfly’s body: long, slender and segmented, each one banded with gleaming sapphire-blue and midnight-black. Its tail curved into a delicate silvery teardrop, like a cerulean brushstroke ending in a pearl drop. Most striking were the eyes – bright metallic green and bulbous.

He wasted no time documenting the marvel. Sketching frantically by daylight to capture wing patterns and venation with watercolor washes of soft pink and charcoal black. In his fieldnotes, he wrote in a flourish:

“Wings like a rose-tinted mirror, edged in obsidian; abdomen a tapering column of cobalt and onyx; eyes that glimmer as though lit from within.”

Professor Larkin painted the four wings laid flat like a delicate fan, each membrane a translucent wash of rose and mauve with a network of fine, ink-black veins. Toward each tip a bold patch of black bent into an inkblot shape, a counterpoint to the gentleness of the pink. The forewings and hindwings matched as if cut from the same ribbon of stained glass, and, as Larkin noted, when the creature moved the light seemed to travel through those veins and shimmer.

The body was a study in slender architecture — a column of alternating cobalt-blue and midnight-black bands that tapered with almost musical precision into a teardrop-shaped tail, the tail itself carrying luminous highlights as if a jeweler had inlaid stone. The thorax was of a bright cerulean blue with cool greenish undertones, a faint teal cast where the legs met he body, giving it a slightly iridescent, aquatic look.

Larkin noted the dragonfly’s behaviour – a gentle hover, a bathetic tumble, and sudden stillness – as if the creature understood the awe it inspired.

Preserved in the entonology archives at Fly Design, the illustration, brushed on thin vellum, shows the dragonfly with wings outstretched, body straight and elegant, colors vivid. Larkin filled pages of his journal with notes on wing-vein structure, habitat flora, and the creature’s seemingly playful drift on the breeze. We are grateful to his commitment

Later found in his field ledger he had numbered the find “Specimen No. 137” and wrote a calm, exact inventory: wing venation, the pattern of black patches, the hue gradients from petal-pink to deeper mauve, the measured gleam of the compound eyes. Ever the scientist, he added a quick Latin suggestion in the margin: Libellula rosaphasma — the roseate apparition.

He signed the page with a smudge of indigo and a note about the Marsh’s “habit of producing the unexpected.”

Note: High quality archival glicée print on acid-free paper, a method that creates fine art reproductions with exceptional color accuracy and longevity. Pigments-based inks are designed to resist fading and discoloration and capture the finest details and subtle color variations with great precision.

Housed in a 4×6” crystal-clear acrylic specimen block, its 1” depth allows freestanding display. Each piece is designed to exhibit on desk or shelf..

Fly Design uses a practice known as entonology — the study of fictitious insects — to reimagine the natural world through scientific storytelling and poetic design.

Specimen No. 137

Name: The Rosy Lacewing of Zelenograd | Libellula rosaphasma

Discovered By: Professor A. Otis Larkin

Date of Discovery: 12 July 1912

Locality: Zelenograd Marsh, Eastern Carpathians, Russia

Catalog No. FD - 24 - 137

12 July 1912, at the edge of Zelenograd Marsh in the Eastern Carpathians, Professor A. Otis Larkin of the Linnaean Society chanced upon an extraordinary dragonfly.

Larkin was a stocky Englishman with an archetypical tweed cap and a penchant for quantum-like footnotes in his journals. He was, by temperament and reputation, the sort of naturalist who married precision to theatricality. His presence at this particular spot was to officially assist Russian counterparts in cataloguing wetland Anisoptera but privately he pursued the rumor of swamp orchids and other fancies whispered in correspondence between Russian and Scandinavian field naturalists. It was on this steamy summer morning, face down in the bog, that Larkin caught sight of a pink shimmering flit above the reeds. He watched, astonished, as the creature alighted on a silver-birch leaf, its gossamer wings catching the dawn light. Intricate veining and lace-like filigree etched into translucent rose-pink membranes were like nothing he’d ever seen.

The Professor was fascinated by this dragonfly’s body: long, slender and segmented, each one banded with gleaming sapphire-blue and midnight-black. Its tail curved into a delicate silvery teardrop, like a cerulean brushstroke ending in a pearl drop. Most striking were the eyes – bright metallic green and bulbous.

He wasted no time documenting the marvel. Sketching frantically by daylight to capture wing patterns and venation with watercolor washes of soft pink and charcoal black. In his fieldnotes, he wrote in a flourish:

“Wings like a rose-tinted mirror, edged in obsidian; abdomen a tapering column of cobalt and onyx; eyes that glimmer as though lit from within.”

Professor Larkin painted the four wings laid flat like a delicate fan, each membrane a translucent wash of rose and mauve with a network of fine, ink-black veins. Toward each tip a bold patch of black bent into an inkblot shape, a counterpoint to the gentleness of the pink. The forewings and hindwings matched as if cut from the same ribbon of stained glass, and, as Larkin noted, when the creature moved the light seemed to travel through those veins and shimmer.

The body was a study in slender architecture — a column of alternating cobalt-blue and midnight-black bands that tapered with almost musical precision into a teardrop-shaped tail, the tail itself carrying luminous highlights as if a jeweler had inlaid stone. The thorax was of a bright cerulean blue with cool greenish undertones, a faint teal cast where the legs met he body, giving it a slightly iridescent, aquatic look.

Larkin noted the dragonfly’s behaviour – a gentle hover, a bathetic tumble, and sudden stillness – as if the creature understood the awe it inspired.

Preserved in the entonology archives at Fly Design, the illustration, brushed on thin vellum, shows the dragonfly with wings outstretched, body straight and elegant, colors vivid. Larkin filled pages of his journal with notes on wing-vein structure, habitat flora, and the creature’s seemingly playful drift on the breeze. We are grateful to his commitment

Later found in his field ledger he had numbered the find “Specimen No. 137” and wrote a calm, exact inventory: wing venation, the pattern of black patches, the hue gradients from petal-pink to deeper mauve, the measured gleam of the compound eyes. Ever the scientist, he added a quick Latin suggestion in the margin: Libellula rosaphasma — the roseate apparition.

He signed the page with a smudge of indigo and a note about the Marsh’s “habit of producing the unexpected.”

Note: High quality archival glicée print on acid-free paper, a method that creates fine art reproductions with exceptional color accuracy and longevity. Pigments-based inks are designed to resist fading and discoloration and capture the finest details and subtle color variations with great precision.

Housed in a 4×6” crystal-clear acrylic specimen block, its 1” depth allows freestanding display. Each piece is designed to exhibit on desk or shelf..

Fly Design uses a practice known as entonology — the study of fictitious insects — to reimagine the natural world through scientific storytelling and poetic design.